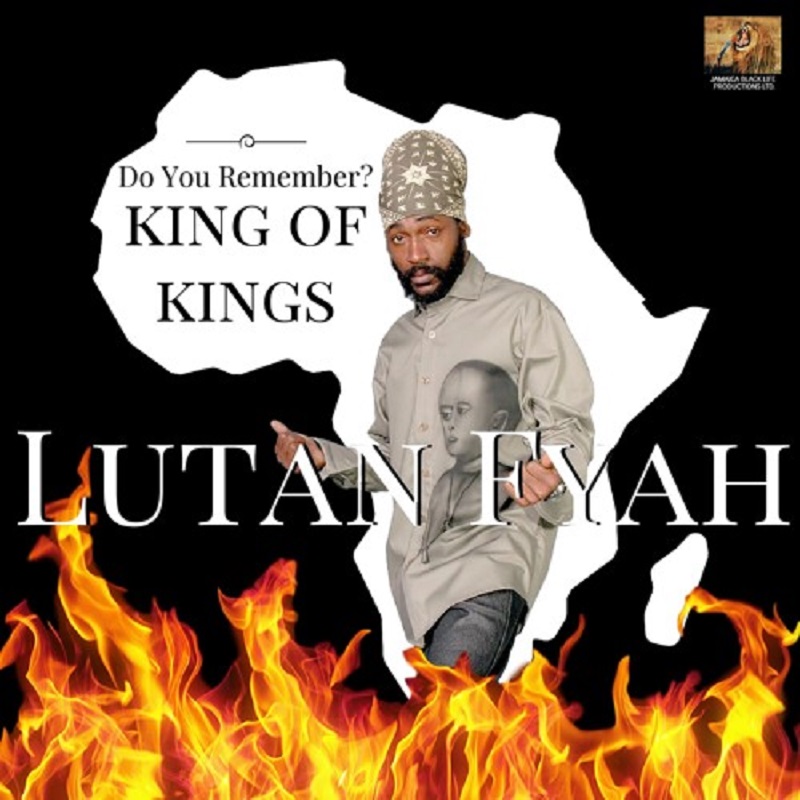

Anthony Martin (born December 1975), better known as Lutan Fyah, is a Jamaican musician and singer.

| Sample | Title/Composer | Performer | Time | Stream |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Khabir 'Kabs' Bonner / Hezron Clarke / Rovleta Fraser / Anthony Martin | 01:20 | ||

| 2 | Jordan Armond / Khabir 'Kabs' Bonner / Shiah Coore / Fabian Francis / Anthony Martin / George 'Dusty' Miller / Earl 'Chinna' Smith | 03:42 | ||

| 3 | Khabir 'Kabs' Bonner / Djenne Greaves / Anthony Martin / Earl 'Chinna' Smith | 03:19 | ||

| 4 | Khabir 'Kabs' Bonner / Fabian Francis / Anthony Martin / Christopher Mercer | 04:27 | ||

| 5 | Jordan Armond / Khabir 'Kabs' Bonner / Fabian Francis / Anthony Martin | 02:47 | ||

| 6 | Khabir 'Kabs' Bonner / Steve Locke / David Malcolm / Anthony Martin | 02:48 | ||

| 7 | Sinima Beats / Khabir 'Kabs' Bonner / Anthony Martin | 03:54 | ||

| 8 | Jordan Armond / Khabir 'Kabs' Bonner / Anthony Martin | 02:56 | ||

| 9 | Jordan Armond / Khabir 'Kabs' Bonner / Anthony Martin | 02:43 | ||

| 10 | Khabir 'Kabs' Bonner / Anthony Martin / Ronen Sabbo / Earl 'Chinna' Smith | 03:59 | ||

| 11 | Kirk Bennett / Khabir 'Kabs' Bonner / Dean Fraser / Djenne Greaves / Othneil 'Neal Tick Man' Halliburton / Steve Locke / Anthony Martin | 03:15 | ||

| 12 | Khabir 'Kabs' Bonner / David Malcolm / Anthony Martin | 04:03 | ||

| 13 | Khabir 'Kabs' Bonner / Jesse Golding / Djenne Greaves / Anthony Martin / Natalie Walsh | 01:18 |

In some ways – like how he never runs out of surprising cadences for even the most challenging riddims – Lutan Fyah is a prototypical modern Jamaican vocalist.

Emerging in the second wave of Rasta’s sustained mid-Nineties assault on slack dancehall themes, the turbaned Bobo Ashanti singjay (born Anthony Martin) is a distinguished member of a select brotherhood of artists that has never sacrificed ideological consistency at the altar of favour in the dancehall. To name a few, artists such as Capleton, Luciano and now Chronixx belong in that group, always acting as a counterpoint to populist dancehall themes and, every few years or so, providing impetus for the pendulum to swing the opposite way.

Having begun his professional musical career recording for Buju Banton’s Gargamel record label in the late Nineties, Lutan Fyah’s career picked up pace in 2001 when he was invited to fill the supporting slot for fellow Jamaican Jah Mason, who was on an international tour at the time. In 2004, he released the album Dem No Know Demself with Gran Canaria Island-based label Minor7Flat5.

It was quickly followed up with Time and Place (Lustre Kings), Phantom War (Greensleeves) and Healthy Lifestyle (VP Records). To date, including PGM’s recent release of Underground to Overground (the initially unreleased album recorded with Buju Banton’s label), his discography numbers in the early teens.

His latest, Life of a King, produced by Khabs “Grillaras” Bonner, is an album of verdant, attentively produced dubby riddims, and features a careening Lutan Fyah at his searing best. Although not quite as rabid as on tracks such as No More Suffering (from 2006’s excellent Healthy Lifestyle), on much of this collection Lutan weaves his singular turn of phrase into precise waves of anger. Whereas before he would wear you down with long strings of cadence, he now chooses the nuances of tone to guillotine Babylon. In totality, Life of a King is an elegant yet strident call to arms. (A 2013 mixtape by French DJ Lorest provides a quick sample of some of his recent work.)

In late December 2013, Lutan made his third trip to South Africa, this time to perform at the True Reflection of Art Festival in Zola, Soweto, organised by the Soweto-based Stepahead Productions crew (a crew centred on building strong community arts structures). He performed alongside local reggae artist Momo Dread and Switzerland-based reggae producer and selector Asher Selector, among others.

The Con caught up with the artist in Zola after his sound check, as he held discussion with local artists. This was on December 22, a day before his performance at the festival. In the 30-minute interview, Lutan painted a picture of Jamaica consistent with the I Wayne lyric “inna slave yard Jamaica / high inflation make blood a run like water”.

In 2005, Jamaica had the highest murder rate in the world (1 674 murders: 58 per 100 000 people), according to a 2007 joint report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the Latin America and Caribbean region of the World Bank.

The numbers began to slide, somewhat, around 2010, in line with a state-of-emergency-like approach to the problem. But without addressing the underlying issues (socio-economic collapse caused by draconian International Monetary Fund and World Bank constrictions, government corruption and the island’s strategic position in the transatlantic drug trade), the situation remains akin to a pressure cooker on this island of around three million people, three-quarters of them black

According to the Jamaican Observer newspaper, 1 200 people were murdered on the island in 2013, a nine percent rise from the previous year. In this context, Lutan’s music, an insider’s call to a militancy springing from self-awareness, remains as relevant as ever.

Lutan Fyah Lyrics

Tell us about the part of Jamaica you’re from. What was it like growing up and what’s it like now?

I’m from [the parish of] St Catherine, Spanish Town. Spanish Town was the first capital of Jamaica in the Spanish colonial times, before the British came. This is the place where I grew up and went to basic school – primary school and high school. At that time when I was growing up it was a lot of fun for me, but as time went on, a lot of violence came up in that part of Jamaica because of gangs.

There was a time in Jamaica when people had jobs, somewhat of an earning. But police have no job when people have jobs. People were able to send their children to school but then police were complaining because there were law-abiding Jamaicans. They raised the price of education so that people had to buy their way to education. They shut down a lot of industries. So a whole generation came and grew up with no jobs, not having proper education. So they actually didn’t know the law. So you had people doing things, breaking the law unconsciously – then the police got jobs.

Poverty was also creeping up in the late Eighties and early Nineties, so my generation grew up jobless. Most of the children in my generation grew up fatherless, homeless – families living with other family members.

Is it a situation where Jamaicans feel they can bring about a political revolution?

We need a serious change, we need people who take the responsibility of minister seriously – not to hustle, not to make money and be a rich guy or a rich woman, but to do their job. In Jamaica, when a guy becomes a politician, they get rich, they become a millionaire after a short while. Yet other people continue to suffer every day from not going to school. So most people’s minds are conditioned to survive and to do anything to survive. Jamaica needs a change but it won’t be by violence, it will be through negotiation and concerted action – people organising for a better life.

In South Africa in the Eighties, liberation movements were banned. But there were strong community structures of people coming together, trying to bring about community involvement in the liberation struggle, be it nurses, social workers or other professionals. There was an umbrella organisation called the United Democratic Front. So while other freedom fighters were jailed, people were still fighting the power from home. What are your thoughts on civil society in Jamaica? Are people active in the knowledge that they can bring about change?

People in Jamaica, I think, just [feel they] need money to survive. They’ll do anything to acquire material items. Nobody cares about making a better Jamaica. People just care about their individual selves.

So do you think dancehall is a mirror of that or does it just perpetuate the situation?

Both. When a man sings about killing, that’s the music a child will grow up listening to. When a man sings about drugs and sex, those messages are all downloading into people’s brains. In the activity of their minds, it manifests. It contributes. Positive music contributes to positive vibes. Negative music contributes to rum drinking, taking pills, smoking hard drugs because you have to wine [dance] and have fun.

Is it easy for an artist like you, who deals with “upful” themes to get rotation in Jamaica, in terms of radio or TV?

If you write good songs and have a good team and have an investor. First and foremost, you have to spend money to make the music and for the brand to reach wherever. It’s easy that way. Then from there, you can sing a song that everybody likes and it just happens. But it’s a payola kind of vibe.

What about other markets like the United States or Europe – do you find roots music is better received there?

It’s more like outside of Jamaica, but our music is nested in every corner of the world. In dancehall, where people are concentrating on the party, it’s just in certain ethnic markets where that music reaches, where people love what’s happening in Jamaica right now. But when it comes to reggae music, it’s more universal. I am able to go to Malawi and do a show. China or Indonesia. I can go anywhere in America and do a show, even if I’m not known, but people will be able to understand what I’m saying and the music is real music, whereas with dancehall, it’s quick and done. I understand it and love it because I’m a Jamaican, I know what it is.

Are there specific artists who you find memorable from your younger days?

Not really, because I just always loved the music. Every Friday we tried to get the new song. Every Friday record shops would be full with people trying to buy that new song. In those days a hit song was really a hit song. It was not really a payola situation because everybody bought that record, and everybody knew the value of that song. They knew what time that song was made, where the song was made, who made it. Nowadays, a song is made here and within two hours my friend in Cape Town has it. Then he sends it to London to his sister, then it reaches his pen pal in North Korea. Then it goes all over.

Now it’s also a visual kind of music, you have to try to brand yourself. So now, you may find me on Instagram, Twitter, Facebook – you name them, Convo, Kite, FaceTime. But those are “friends” and not fans – people who might not necessarily be coming to your concert because they have to go to work from Monday to Friday, so they use Instagram to occupy their time. This is what is happening today. You can find Lutan Fyah in every cubicle and corner where the music is played, with people who connect with me telepathically or spiritually, not by seeing me on Facebook or Twitter every day.

So you’re not really obsessed with that form of marketing?

I am. I am. But high high, I’m not. But me, the image, is. But the spirit is not a part of all that. I have to do the internet because people want to know where Lutan is, how to get hold of him, what is he doing now – this is how Lutan makes a song, this is what he talks about, this is what he eats. These things are for “friends”. And for my fans, I use my spirit. I can go to Guinea Bissau and sleep in a mud hut, and cook with wood fire. I can also be in Soweto, I can be in the Sheraton, I can be in the Hilton. I can drive around in a limousine. I can take a Bug. Friends can pick me up. It’s the life of a king.

So when you’re on the road travelling and performing, how easy is it to maintain your lifestyle in terms of what you eat or what you would like to eat?

It’s complicated sometimes, but I drink fruit juice for today if I can’t eat vegetables or whatever I’m eating. I won’t die by the morning. I will find nuts tomorrow. I don’t worry about food. See, I don’t write my music.

So you don’t put pen to paper?

No. So I fast every day. There is always a period of my day where I’m not concentrating on food. I forget about the stomach and I keep my head still. So food is not a problem.

You’ve got quite a few albums already. From what I can tell, a lot of people in Jamaica record very often and quite quickly. Is it the competitive nature of the industry there? How does one account for the output?

It’s competition and then Jamaica doesn’t have an industry, like an [infrastructurally solid] industry that locks down everything that is happening in the music business. It’s like a few people have a group that is organised to industrialise what is happening, to connect groups and sectors of people. So people are always pushing what they have. The artist has to keep consistent in that kind of environment, because a lot of people make music every day. That’s the competitive part. And for people to continue hearing you and seeing you, you have to continue to make music. This is how it is in Jamaica. And I don’t hope for a change and I’m not trying to change anything because, as for me, I don’t care to do music every day. I’m doing what I can do and how I can do it. I have to create that family unit, so that when I’m old, I still love people and people still love me. Personally. Not because ‘he was my artist and this is my artist now, I don’t like how he’s chilling, so I don’t like him again’. I don’t want that to happen to me. Lutan Fyah is different from Anthony Martin – totally.

I’d like to ask you about one particular album, Healthy Lifestyle. My interest in it is that it was produced by the late Philip ‘Fatis’ Burrell, one of the greatest producers of contemporary reggae music. When I compare it to other albums, the riddims are particularly interesting. What was it like working with Burrell on that album?

We would make the music and Fatis just corrected it. He doesn’t care what you want to do. He lets you make what you want to do. He finalises and rebirths the song in the morning. Because if he’s there, he’s gonna be telling you to do too much. So he’d sit in private and edit. It was the last days of his life when I met him, so we give thanks for it, Healthy Lifestyle.

So you say he was a minimalist in terms of giving an artist instructions?

Musically, you could play what you wanted to play, but he would not tell you what he wants you to do. He would also give an idea and come up with a melody, a word and a few lines. He was a great producer. He was one of the greatest I’ve recorded with.

There’s a new crop of Rasta artists in Jamaica, people like Chronixx and Jah9. Considering the popularity of dancehall in the country, do you think they can be able to break through commercially or do you think they might struggle?

I pray that they can break through, because it’s what I prayed for, to see young minds come up. It’s always a struggle but this is one of the best things that has happened to the music in a long time.

When you were coming up as a youth, how did you get introduced to Rastafari?

It was just the word and sound through the air, passing by hearing reggae music, seeing Rasta people. And then I was in school and I just found myself starting to say, “Rastafari”.

So by the time your football career kicked off were you already a Rastafarian?

I played football in the big leagues as a Rasta. I was a long natty. I was playing as a Rasta among baldheads.

What was that like? Did you get bad looks?

Rasta always gets bad looks and criticism and people laugh at you. “Where’s your comb?” “Dread, you weak, you want some salt?” “Dread, you want some pork oil?” After a while, Rasta stopped playing football in Jamaica and yet we were the magicians of the game. We used to do everything – blind passes and so on… But music was an easier calling for me. In terms of my culture, Rastafari, there were a lot of things I wanted to say that were spiritual and music was my forum. I used music and music used me.

What’s your feeling about the general quality of production coming out now in Jamaica?

Boring.

Boring? Why?

It’s not sounding original. It sounds like we’re following something, you know, and people normally follow what we [Jamaicans] do. It’s good to follow what Americans are doing. Black culture follows black. But I think we choose to follow the most degenerate part of our culture. So people follow the wrong thing and promote the wrong thing. I think we need to go back to the royal form of the music, where we can sing songs to liberate people. Reggae represents the abandonment of all negativity in the world.

You have set up a youth foundation. What does it do?

The Youth Upliftment Foundation is all about what I’m talking about now. It’s about upliftment of people, mentoring, setting up workshops, knowing that you’re an example and role model to children. We’re not superstars. We’re not Batman and Robin. We’re not Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. We’re brothers coming from the same situation, same condition. We could be walking up and down with an AK-47 because that’s what we see – killing, shooting every day. But we choose to do what we have to do – be positive role models. That’s what we want to mentor to the youth. It’s a mentoring kind of thing for youths who are homeless, fatherless, mother-alone and father-alone children. It can depress them, that mind state.

I’ve been in Jamaica but I’ve been talking to you since before I was born. I see youths like you [pointing to people in the room] and you and you every day in Jamaica.

All photographs by Hugh Mdlalose